Design systems solve a lot of problems

They give teams a shared language, maintain consistency, improve accessibility, and speed up product development.

But they also create a new problem...

How do you get all that design system knowledge into the hands of developers actually building features?

Right now, most teams do it manually. A designer creates specs in Figma. Someone writes a user story transcribing those specs into Jira. A developer reads that story and tries to match the design using components from the UI kit.

It works, but it's slow. And inconsistent. Every person writes user stories differently. Details get lost in translation.

AI tools promise to help

But if you've tried using Claude or ChatGPT to generate user stories from design screenshots, you know the results are generic. The AI has no idea what components exist in your design system or how to use them properly.

Model Context Protocols (MCPs) change this

An MCP can give your AI agent direct access to your design system. Not just screenshots or descriptions, but actual component APIs, prop definitions, and implementation details.

I've been testing this workflow at Headway, and I want to show you what actually works, what the limitations are, and how this compares to what tools like Figma are building.

- IMPORTANT NOTE -

With the pace of how things are evolving within agentic work, MCPs, and the AI tools, it's important to remember that this article is a "moment in time" and that some of the things you read here or watch in the video below may be outdated. And that's okay. In my mind I wanted to share our mindset and approach to how we've been trying to tackle these problems with the clients we collaborate with.

As always, design and development tactics are always a work in progress. As long as you have the right approach to guide your evolving processes, you'll make improvements with teams.

Watch my presentation or keep reading

I breakdown and walk through everything in this article in my video presentation on design system MCPs and the experiences we've had with them so far (November 2025) at Headway.

The design handoff problem

Design systems deliver real benefits. They create consistency across products, establish accessibility standards at the foundation, make products more maintainable, and accelerate development by solving problems once instead of repeatedly.

But they also introduce challenges.

You need to uphold the standards you establish. If your design system says buttons should work a certain way, every team needs to implement buttons that way. Enforcement takes effort.

The bigger challenge is context. How do you make sure developers know which design system components to use and how to use them correctly? This is where user stories come in.

What a good user story needs

A well-written user story has three main parts:

1. The statement (who, what, when)

This defines who needs what and when they need it.

Example: "As a signed-in user, I need quick access to main sections within the app."

2. Acceptance criteria (what done looks like)

This defines when the feature is complete. What does the engineer need to build? What will QA test against? How do you know when this task is finished?

3. Context and notes (design specification)

This is where things get detailed. A good user story includes:

- A screenshot of what you're building

- Sample implementation code that references your actual design system components

Not generic HTML. Not made-up component names. Real references to your UI kit.

For example

instead of generic <div> and <button> tags, the story should reference your Logo component, your Text component, your MenuItem component. It should use the language your design system established.

This helps developers implement the design accurately without hunting through Figma or guessing which components to use.

The question is: how do you generate user stories at this level of detail without doing it all manually?

What doesn't work well

Let me show you three approaches that fall short before we get to what actually works.

Manual transcription

The traditional way: look at the design in Figma, identify every specification (font sizes, spacing, component states, menu items), and manually type it all into a Jira story.

This works. It gives developers all the information they need. But it takes time, and consistency varies based on who writes the story.

AI without context

Add Claude to the workflow. Upload a screenshot and prompt: "Write a user story for this design. Include React and Tailwind implementation."

Claude generates something, but it's generic. Every element from the screenshot appears in the output, but nothing ties back to your design system. The suggested code uses basic HTML elements, not your actual components.

This is faster than manual transcription, but lacks the accuracy developers need.

AI with partial awareness

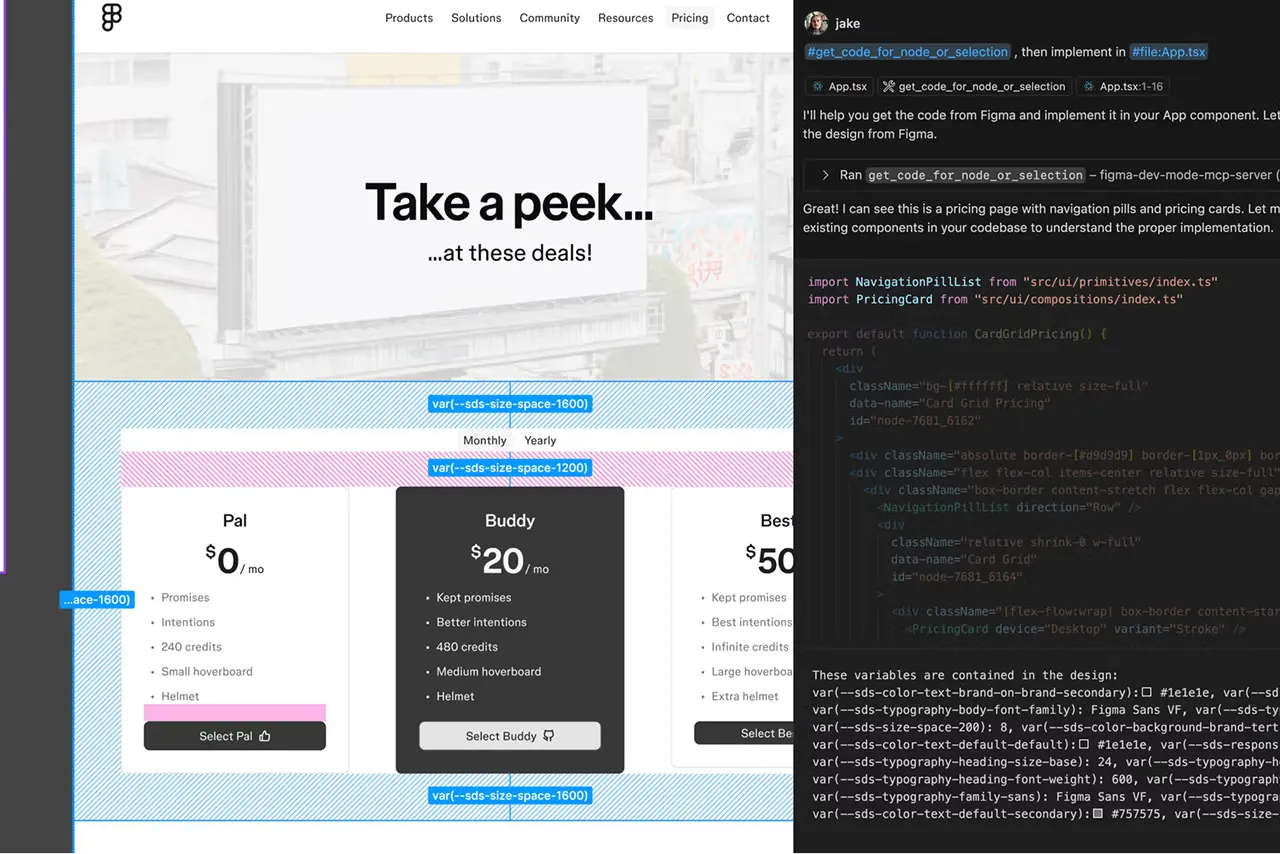

Use Claude Code with a more specific prompt: "Implement this design from Figma at [file URL]."

This signals Claude to reach out to Figma's MCP server for context. In my testing, I hit authorization issues and couldn't fully connect, but Claude knew it was a Figma file and walked me through questions about the design.

The output was closer to what I needed. Still not perfect, still lacking full design system context, but noticeably better than a generic AI attempt.

None of these approaches give us what we really need: AI-generated user stories that reference our actual design system components.

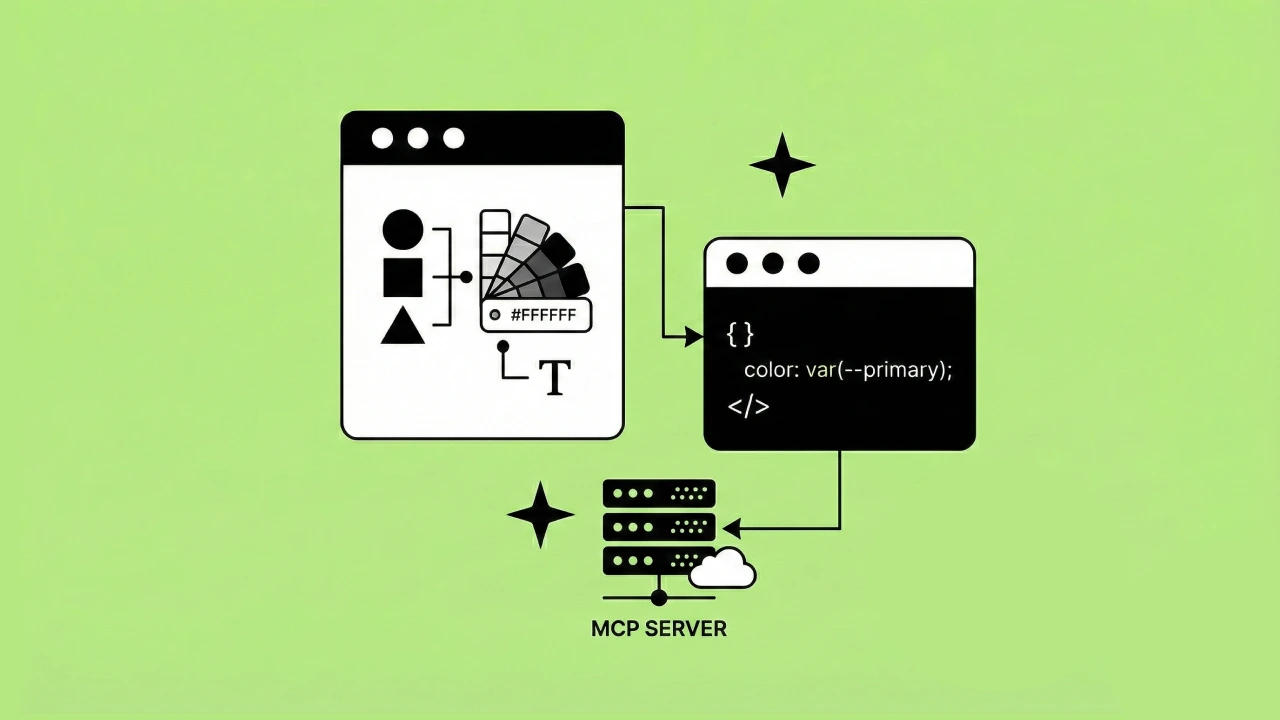

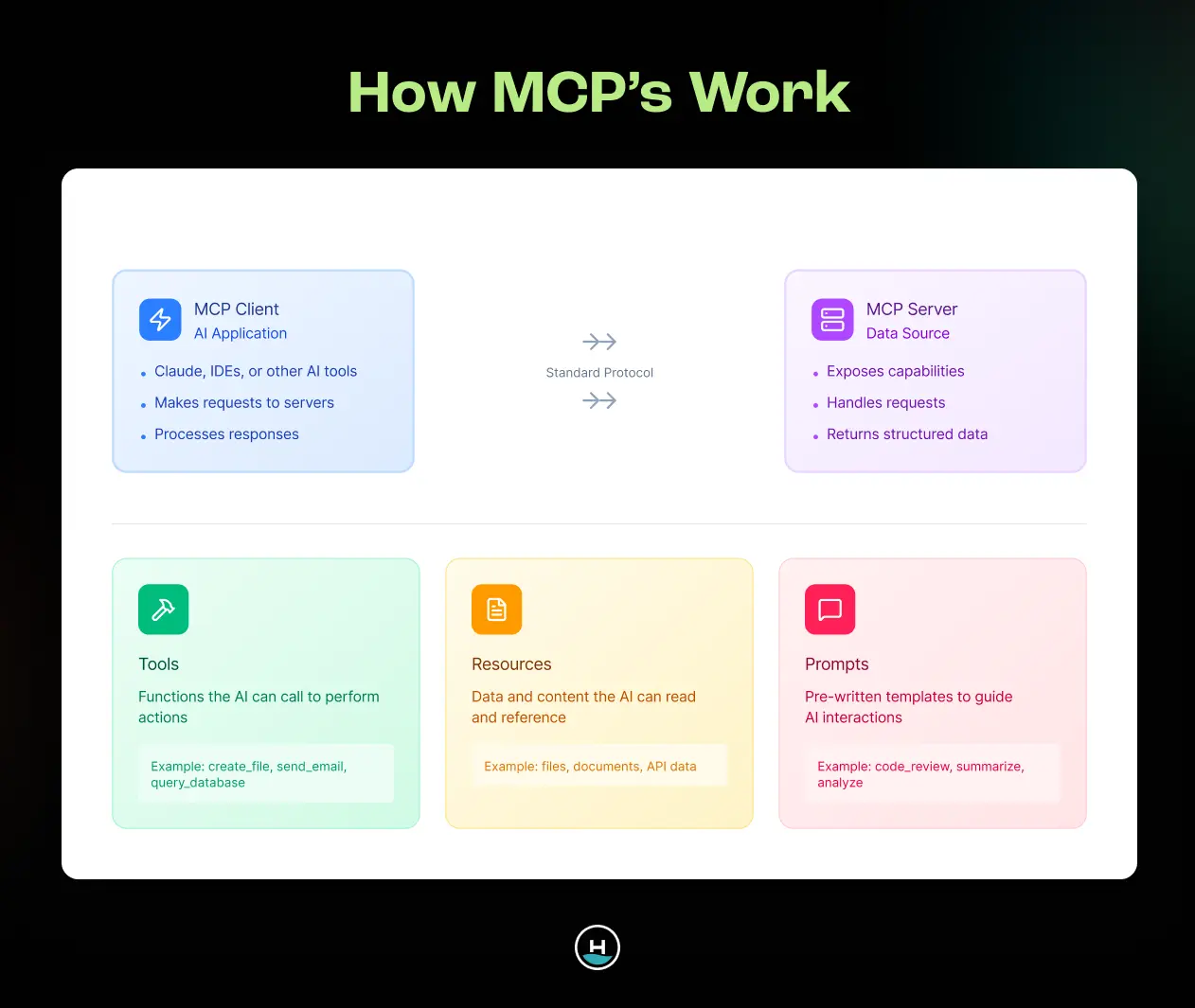

What works: Model Context Protocols

An MCP creates a standardized way for AI agents to access external context.

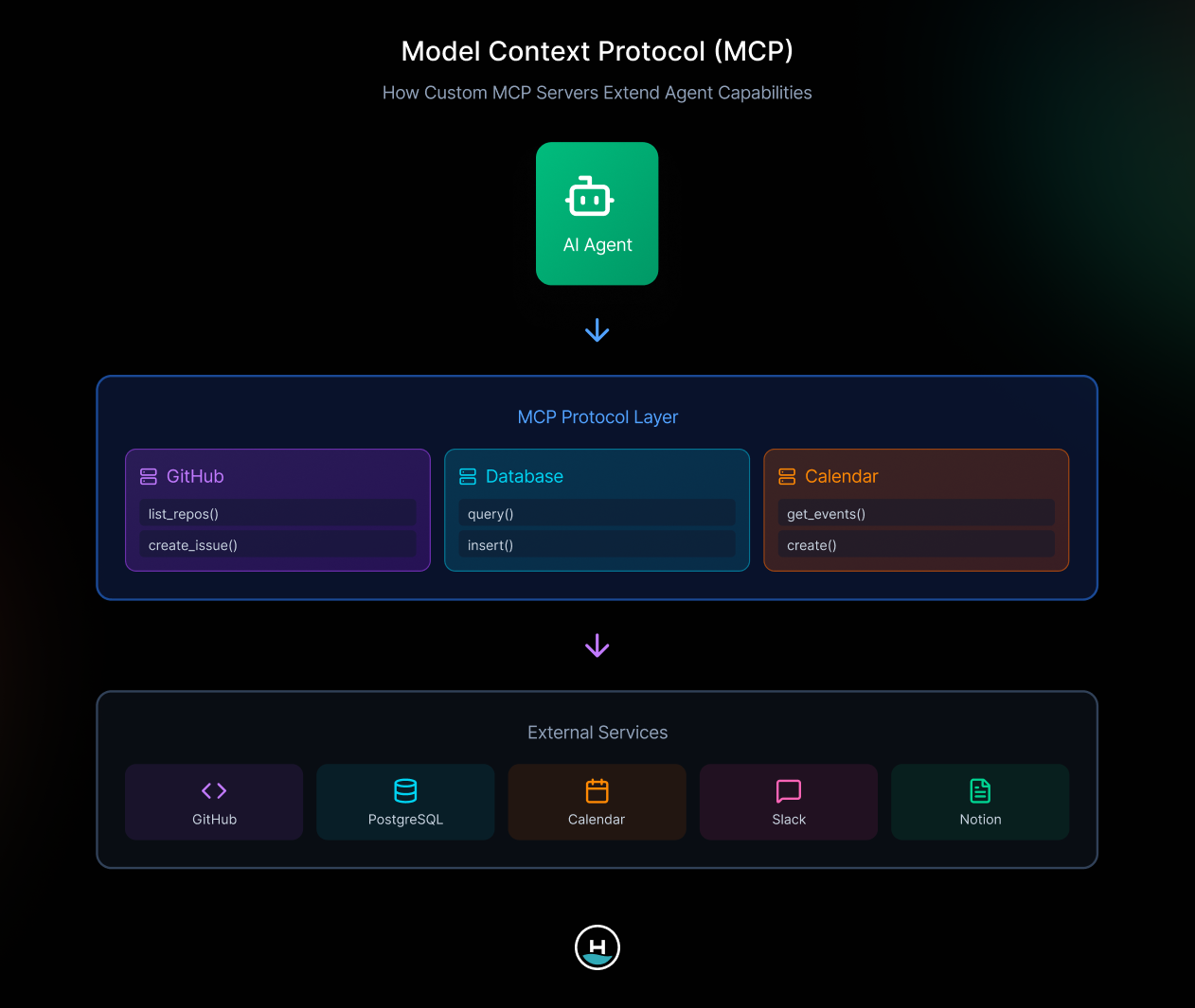

Think of it as a bridge. On one side, you have your AI agent (Claude Desktop, Claude Code, VS Code, or other MCP clients). On the other side, you have servers that provide context (design systems, GitHub, databases, calendars, Slack, Notion, or anything else you build).

The protocol defines two transport methods. Standard IO for locally running servers, and HTTP for hosted servers you access over the network.

MCPs provide three utilities

1. Tools perform functions

They take arguments, do work, and return output.

2. Resources provide static context

Think of these as read-only documents that help the agent understand something.

3. Prompts trigger specific MCP features

When you say "implement this design at [Figma URL]," that prompts the agent to use Figma's MCP capabilities.

This architecture is powerful because it's extensible. You can build your own MCP server or use existing ones. The agent just needs to know when to trigger which tools.

Design system MCPs in action

Here's what happens when you use a design system MCP like our custom Shipwright MCP.

The prompt: "Write a user story for this design using Shipwright UI for implementation."

The output is almost perfect. The generated JSX references actual design system components: Avatar, Logo, Text, MenuItem, Icon, Container. These aren't generic elements. They're the specific components from our UI kit with the right props and specifications baked in.

This is what we want. A user story that guides developers directly to the right components without making them figure it out themselves.

How it provides design system context

Our custom Shipwright MCP uses two simple tools to deliver accurate results.

list_components returns all components available in Shipwright UI.

get_component_details provides typing and prop information for specific components.

When you ask the agent to write a user story using Shipwright UI, it calls these tools to understand what components exist and how to use them.

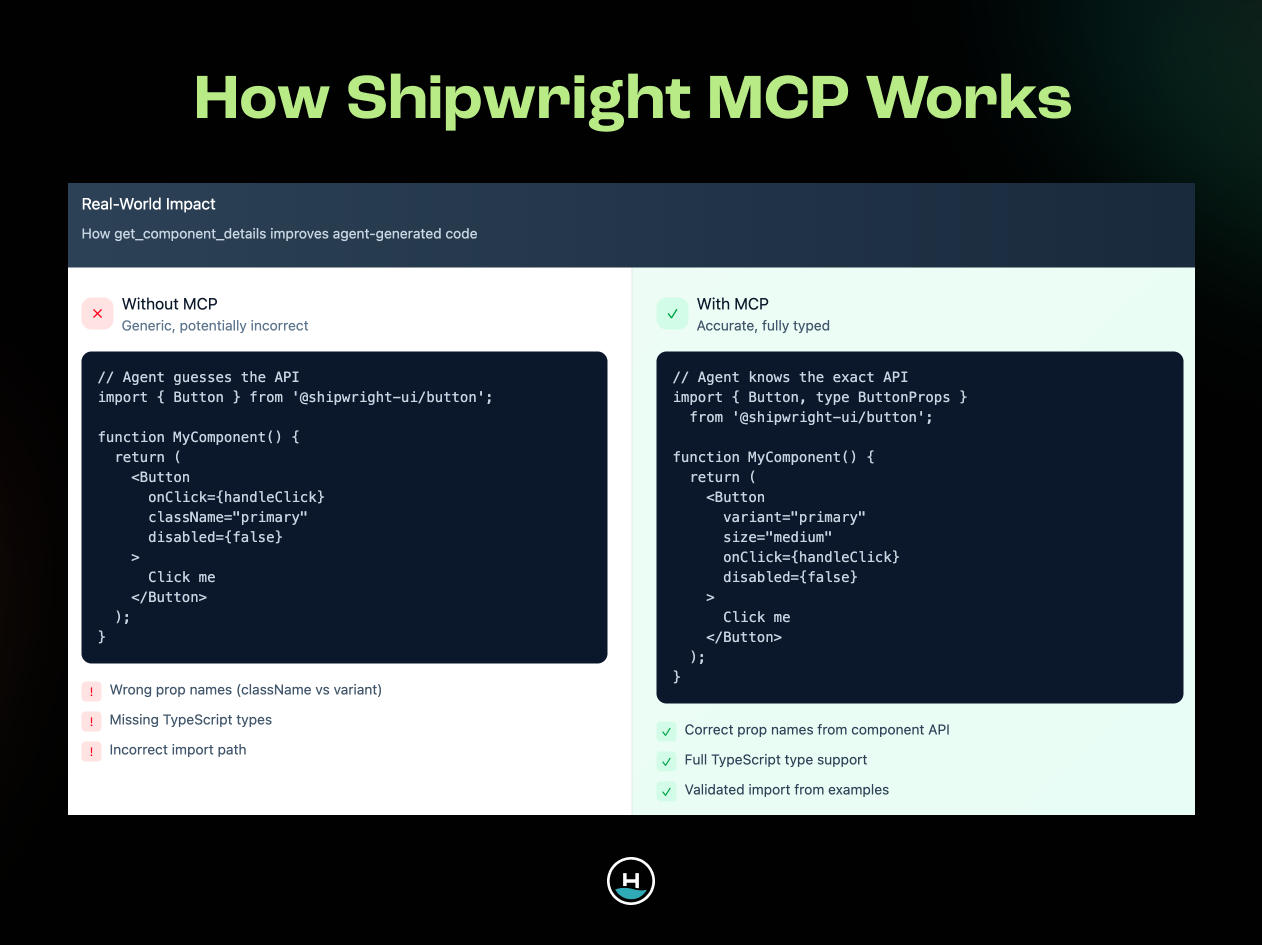

The agent sees you need a menu item. It checks Shipwright MCP and learns there's a MenuItem component with specific props. It suggests implementation using that actual component instead of guessing with generic HTML.

That's the difference. Without MCP context, the agent generates a generic button with onClick, className, disabled, and enabled states. Technically correct, but disconnected from your design system.

With MCP context, it generates a Button component with variant, size, onClick, and disabled props. Specific to your design system. Directly usable by developers.

How this compares to Figma's approach

Figma isn't sitting still. They're actively improving their own tooling to solve this exact problem.

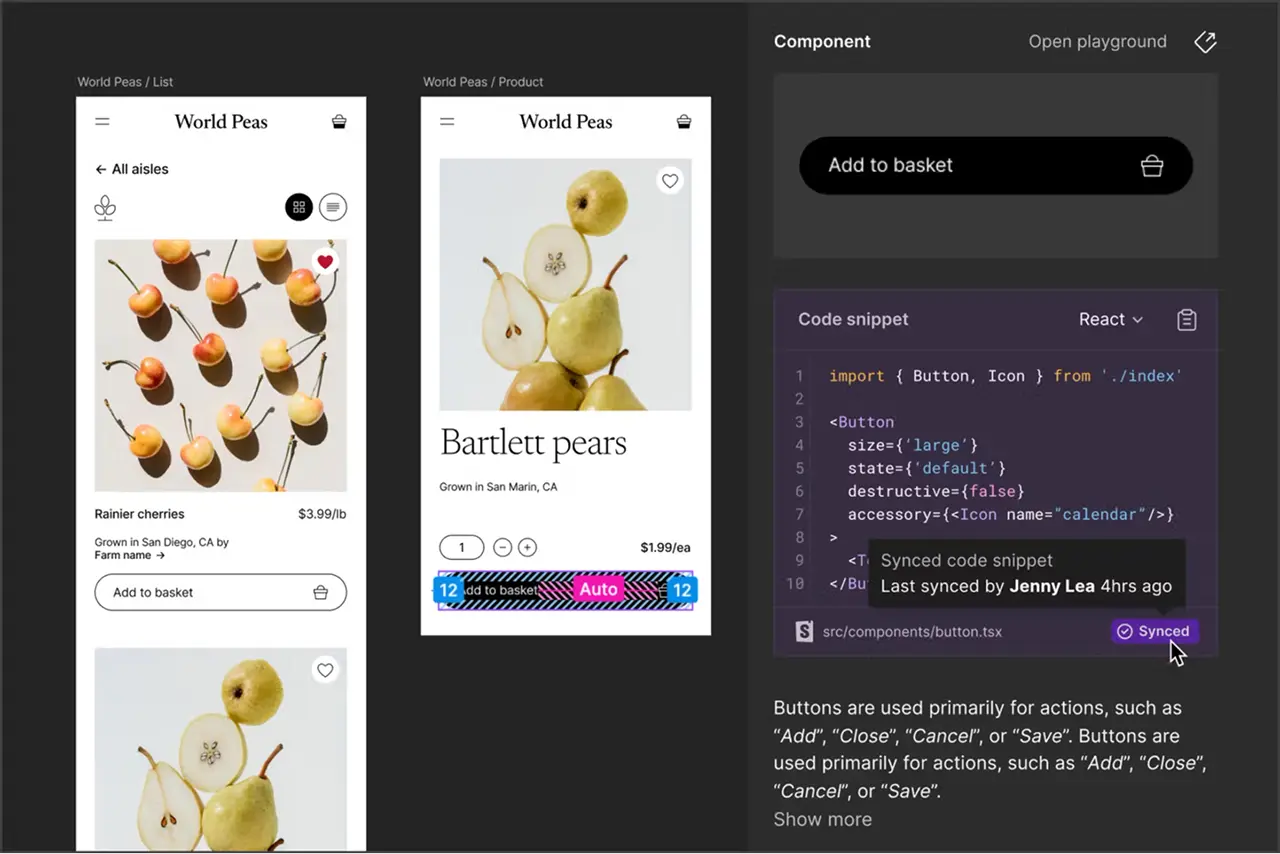

Code Connect

Code Connect matches designs in Figma with your UI kit implementation. It provides design system-informed code snippets directly in Figma.

You can interact with component definitions in a playground, adjust properties, and see the resulting JSX before touching your codebase. It's fast and low-cost for developers to experiment.

This is genuinely useful.

Figma's MCP server

Figma recently launched their own MCP server. It uses Code Connect information to inform AI agents about your component APIs.

The workflow: design in Figma, develop your UI kit informed by those designs, bring that UI kit information back into Figma via Code Connect, then Figma's MCP exposes that context to your agent.

It's a full circle that requires ongoing maintenance. You need to keep Code Connect updated with your UI kit changes. You need to teach Figma what your components are and how they work.

There's also cost. To use Figma MCP, you need a dev or full seat in your Figma organization. That's an additional expense.

In early testing, the output quality from Figma MCP isn't noticeably better than what we get from Shipwright MCP. But Shipwright MCP has no added cost or maintenance overhead.

Why we're exploring custom design system MCPs

After initial testing with both approaches, we're leaning toward design system MCPs over Figma MCP for a few reasons.

1. No additional cost

The MCP server looks at your UI kit packages directly. No new subscriptions required.

2. No maintenance overhead

We don't need to keep Code Connect synchronized with our UI kit. The MCP reads component definitions directly from the source.

3. Portability

If we switch from Shipwright UI to Material UI or another kit, we don't need to reconnect everything in Figma. The MCP approach works with any UI kit.

This makes it more future-proof and adaptable to different projects with different design systems.

Practical implementation considerations

Setup is faster than you think

The technical setup is straightforward. If you're using an existing MCP server like Shipwright MCP, you need a copy of that code on your machine. Then you configure your AI agent to use it. Configuration is about 10 lines of JSON. You tell the agent where the MCP server is running or where it lives on your file system. You grant permissions if needed.

That's it. The whole setup takes about 10 minutes on a call with someone.

Compare that to Figma MCP, where you also need to ensure proper permissions within your Figma organization and maintain Code Connect mappings.

Limitations to keep in mind

This approach isn't perfect. Here are some important things we've realized working through this.

LLMs aren't deterministic

One benefit of design systems is consistency. You want the same input to produce the same output every time. But LLMs don't guarantee that. If you give the same Figma URL and the same design spec to your agent on Monday and Tuesday, you might get slightly different results. MCPs help minimize this drift by providing consistent context, but they don't eliminate the problem entirely.

Permission and access

Adding another tool to your workflow means another layer of permissions to manage. You need organizational approval to use AI agents in the first place. Then you need to ensure your MCP servers have proper access to the resources they query. Not impossible, but it's a hurdle to work through.

Perception and expectations

The JSX code in your user story isn't meant to be copy-pasted and shipped. It's meant to guide developers toward the right components and save them research time. This is a tool to accelerate implementation, not replace engineering judgment. Managing expectations around that takes communication.

Is this worth trying?

Design systems create shared language and consistent standards. But getting that knowledge into development workflows has always required manual effort. MCPs provide a way to automate that handoff without sacrificing accuracy. Your AI agent can reference actual design system components when generating user stories. Developers get clear guidance pointing them to the right UI kit resources.

This isn't about replacing engineering work.

It's about removing the research step and helping developers implement designs faster with fewer translation errors. We're still early in testing this workflow, but the results are promising enough to keep exploring. Especially as MCP tooling matures and more design systems build their own servers.

If you're working with design systems and feeling the friction in handoffs between design and development, this is worth experimenting with.

And if you're looking for some help on this problem we're happy to support you.

Schedule a free consultation to see exactly how Headway could help you and your team with this.